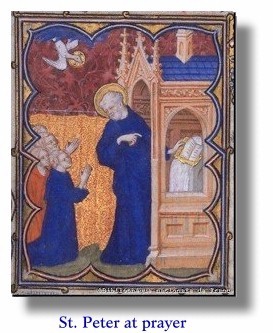

A Sermon for

the feast of

Saint Peter

by the Rev. Dr. Robert Crouse

"Simon, Simon, behold, Satan hath desired to have

you,

that he may sift you as wheat.

But I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not."

Our

Christian Year is punctuated by the festivals of saints: Apostles

and Evangelists, Martyrs and Confessors; holy men and women, and

children, too, of all times and places, of all sorts and conditions.

These festivals set before us, in a splendid panorama, all the

Spiritís gifts, the virtues and the graces of Godís Kingdom, in

their marvelous diversity. They remind us, by their different

emphases, that though there is "one Spirit and one hope, one Lord,

one Faith and one Baptism, one God and Father of us all," yet our

holy calling is expressed in so many different ways. "As the body is

one, and hath many members, and all the members of that one body,

being different, are one body; so also is Christ."

Our

Christian Year is punctuated by the festivals of saints: Apostles

and Evangelists, Martyrs and Confessors; holy men and women, and

children, too, of all times and places, of all sorts and conditions.

These festivals set before us, in a splendid panorama, all the

Spiritís gifts, the virtues and the graces of Godís Kingdom, in

their marvelous diversity. They remind us, by their different

emphases, that though there is "one Spirit and one hope, one Lord,

one Faith and one Baptism, one God and Father of us all," yet our

holy calling is expressed in so many different ways. "As the body is

one, and hath many members, and all the members of that one body,

being different, are one body; so also is Christ."

"There are diversities of operations,

but it is the same God that worketh all in all." We have our unity

in and through diversity. That is the pattern of the Churchís life,

and that is the pattern of all true social order: a gracious

reciprocity of gifts and talents; unity in diversity.

Both sides of that are crucially

important: both diversity and unity. All our diverse gifts have a

common source, and must serve a common end; all express and serve a

common faith. Thus this great festival of St. Peter comes in the

midst of the Christian Year, as a festival of faith - that virtue

upon which all the rest, all the gifts and graces of the saints must

hinge. All the rest must hinge upon that faith, that Petrine

affirmation, "Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God." That

is the foundation of all the divers Christian virtues, the ground of

Christian unity, the "rock" upon which the Church of Christ is

built; all Christian life begins with that, and hinges upon that.

And we who keep St. Peterís festival must celebrate and share St.

Peterís faith.

But is such clear and confident

assertion really possible for us? Amid all the complications of our

lives, amid all the conflicting voices that assail us, from outside

us and from within our own souls, can we be so definite as that?

Surely, we think, surely it was easier for those first followers of

Jesus. If we had heard Jesus teaching, if we had witnessed his

miracles ourselves, surely faith would be an easy matter. So we tell

ourselves.

But, you know, practically every page of

the Gospel contradicts that sentiment. Faith did not come easily.

The lame walked, the lepers were cleaned, the blind received their

sight, the dead were raised, and the poor had the Gospel preached to

them. The signs of divine presence were all there. But the people

heard and saw as though they had neither eyes nor ears. They were

disturbed, and cast about for explanation: "He casteth out the

devils through Beelzebul," they said, "the prince of devils". There

was great popular excitement, to be sure, but the excitement served

only towards Christís rejection.

Even his closest friends hesitated when

he asked them what they thought. "Some say that thou are John the

Baptist; some say Elijah, or Jeremiah" - some great prophet, risen

from the dead. Yes, "but whom do you say that I am?" It fell to

Simon Peter - Peter the impetuous - to rise to the great

affirmation: "Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God." "And

Jesus answered, saying, ĎBlessed art thou, Simon, son of Jonas: for

flesh and blood hath not revealed it unto thee, but my Father, which

is in heaven.í"

It wasnít easy and I donít think it

became much easier. There at Caesarea Philippi, we see one side of

Peterís faith: the moment of faithís clear affirmation: "Thou art

the Christ, the Son of the living God." A little later, in

Jerusalem, on the night of Christís betrayal, we see another side.

Still, there is the confident assertion: "Lord, I am ready to go

with thee, both to prison and to death." But that very night, at the

hour of cockcrow, there came the moment of denial: "I know him not",

said Peter, as he warmed himself by the fire. And the Lord turned,

and look on Peter, and Peter remembered how the Lord had said to

him, "before the cock crow, thou shalt deny me thrice." And Peter

went out, and wept bitterly.

All this, you see, belongs to Peterís

fatih: the warm, clear light of affirmation, the dark cold night of

doubt and hopelessness, and then the tears of penitence. St. Peterís

faith is sorely tried and tested. "Simon, Simon, behold, Satan hath

desired to have you that he may sift you as wheat. But I have prayed

for thee, that thy faith fail not." And, in the end, the faith of

Peter does not fail; in the end, it is affirmed again, in tears of

penitence.

We who share St. Peterís faith must also

know and understand the trial of our faith. We walk by faith, you

know, and not by sight. We see darkly, through a glass, as in a

clouded mirror; we know in part. There is, indeed, the moment of

confident assertion: "Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living

God", but there is also the moment of doubt, and manifold

temptation, the moment of denial and betrayal, when we say, "I know

him not." And then our Saviour turns and looks upon us, and faith

returns, in tears of penitence.

I think it is vitally important that

Christians nowadays should have some understanding of the meaning of

the trials of our faith. Around us, not only in the world, but

within the Church itself, and within our very souls, there are the

pressures of insistent worldliness. The hosts of compromise and

shallowness besiege the very rock of faith. 'Adjust, revise,

conform', they cry. "Surely thou are one of them", they cry, "for

thy speech betrayeth thee." And how often, sorely tempted, do we

reply, "No, I know him not". Then may we find the grace of Peter to

shed the bitter tears of penitence.

St. Peters shows us that there is no

easy Christian faith. Trials and temptations, the dark night of

doubt, confusion and uncertainty, are not just unfortunate

accidents. In Godís good providence, they belong to the very life of

faith; for faith must be tried, like precious metal, "which from the

earth is tried, and purified seven times in the fire". Do not

suppose for one moment that we can avoid the testing. Indeed, as St.

James says in his Epistle, we must "count is all joy...knowing that

the trying of our faith worketh patience." "Let patience have her

perfect work", he says, "that ye may be perfect and entire."

Christian times are always times of

trial. Perhaps those trials take different forms in one age or

another, and different forms for each of us; but always they are,

and must be there. Doubt and confusion - even the moments of

betrayal - do not destroy the soul which is ready to return in

penitence. What alone destroys the soul, is the cold, hard cynicism,

which blasphemes against the Spirit; which simply doesnít care.

"Simon, Simon, behold, Satan hath desired to have you, that he may

sift you as wheat. But I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail

not."

Cling to the rock of St. Peterís faith,

and "count it all joy"; "Let patience have her perfect work." That

rock will not fail us; we have our Saviourís promise that "the gates

of hell shall not prevail against it."

Amen. +

+ + + + + + + + + + +